Māori sailors were among the first New Zealanders to see the world – long before organised colonisation, the Treaty of Waitangi, or even widespread European settlement.

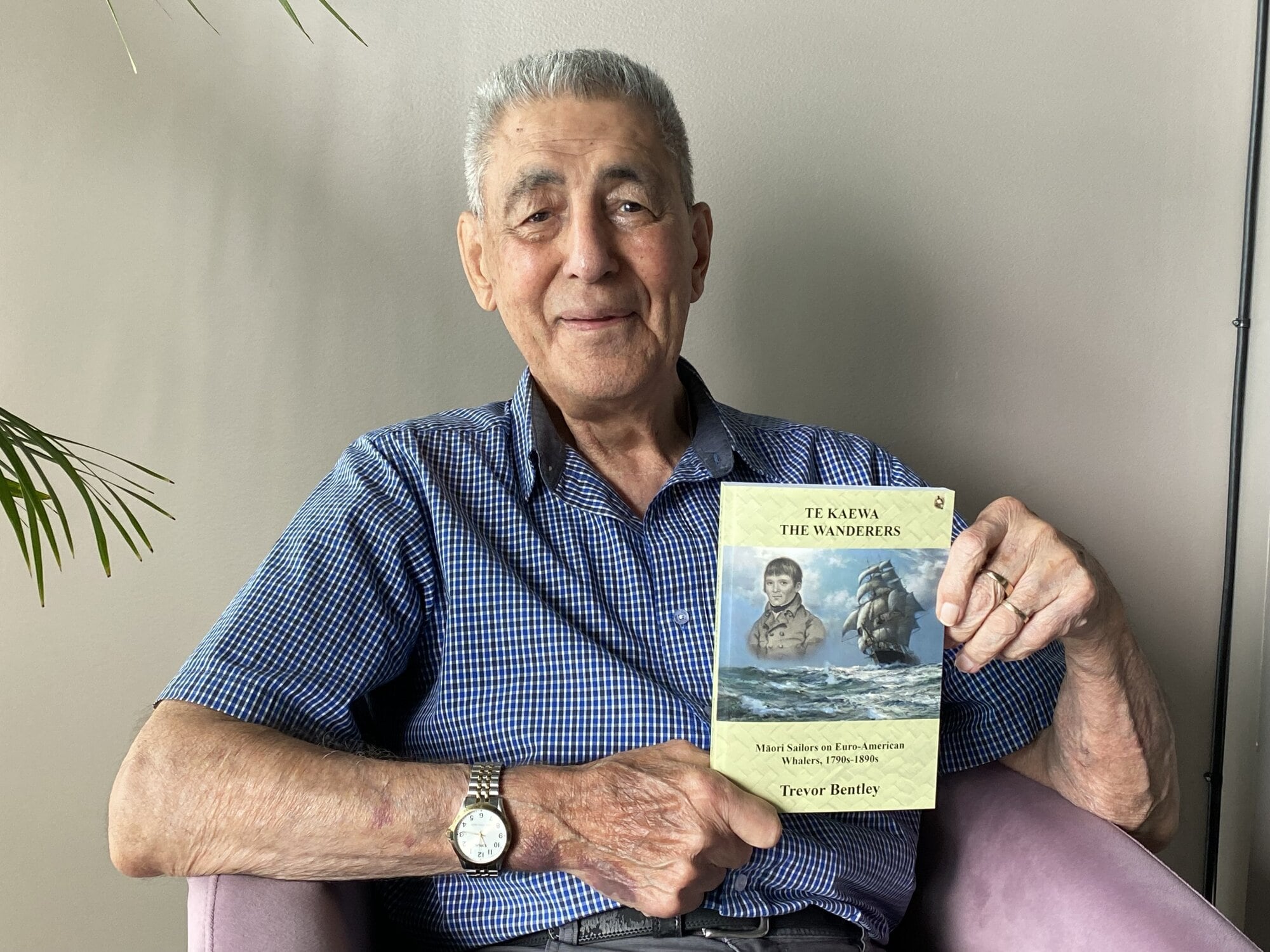

That extraordinary but largely forgotten story is brought back to life in a new book by Tauranga historian Trevor Bentley, titled Te Kaewa – The Wanderers: Māori Sailors on Euro-American Whalers, 1790s-1890s.

The book traces more than a century of Māori involvement in the brutal, dangerous and global whaling industry, beginning as early as the 1790s – decades before British sovereignty was declared in New Zealand.

The American whaler Charles W. Morgan. During its Pacific cruises between 1845 and 1904, its multi-racial crews were described as including Kanakas (Pacific Islanders), Cape Verdeans, Seychellois and New Zealanders as Māori were then known. Photographer unknown, ‘The Charles W. Morgan’, 1920. Courtesy of the Mystic Seaport Museum. Mystic, Connecticut, U.S.A.

“They were the first sailors aboard the first American and English ships that turned up on the New Zealand coast,” Bentley said.

“This is really early history – far earlier than most people realise.”

As Euro-American whalers poured into the Pacific from the early 19th century, they were chronically short of crew. Disease, accidents, desertion and violence meant sailors “died like flies”, Bentley said.

“They fell out of the rigging, got washed overboard. Life expectancy on whaling ships wasn’t high, and the crews could be lawless – they sometimes fought, murdered each other, and clashed with indigenous people almost everywhere they went.”

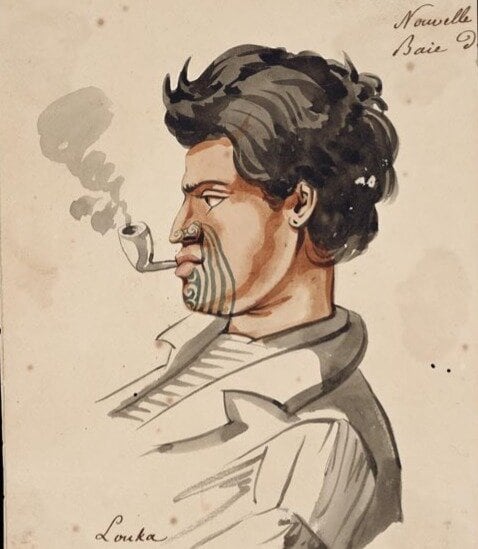

After boarding a French whaleship in 1833 Hone Tikao (John Love) visited Europe and travelled in France Germany and England. Photo / Charles Meryon, ‘Tikao, natural d Akaroa’ NGA 9126. National Gallery of Washington. Wikipedia Commons.

That shortage of manpower created an opening for Māori and other Polynesian sailors – and Māori quickly earned a formidable reputation.

“They were very competent, very able sailors,” Bentley said. “They were used to handling small craft, surf, and sails. They could swim like fish – and most of the whaling crews couldn’t swim at all.”

That confidence translated into fearlessness in the most dangerous jobs, particularly as harpooners, topmen who worked high above the mainsails and boat crew chasing whales in small craft.

The cover of the book Te Kaewa – The Wanderers: Māori Sailors on Euro-American Whalers, 1790s–1890s by Trevor Bentley. Photo / Rosalie Liddle Crawford

“Some historians say Māori fearlessness came from the confidence that they couldn’t drown,” Bentley said.

“Observers were astonished at how long they could stay submerged, or how far they could swim.”

Their skills, courage and humour made them highly sought after.

“In the most dangerous conditions, waves sweeping the decks, Māori sailors could still grin, crack a joke and get their mates laughing. Captains loved recruiting them because of the positive effects most had on crew morale.”

Bentley’s book is filled with vivid individual stories drawn from ship’s logs, court records and eyewitness accounts. One is Hone Tuati, known to his shipmates as ‘John Sac’, who sailed with the United States Exploring Expedition in the late-1830s, travelled the world, and became one of the first Māori known to have seen Antarctica.

Across the globe

Another is Te Anaru, a Tauranga man whose name meant “the brave”. He left Tauranga aboard a whaler, based himself in Sydney, and later returned in the 1860s with a Pākehā wife, settling back in a local pā. He was sketched by military artist Horatio Robley, and the drawing appears in the book.

‘Louka’ in Sydney 1847. Photo / Leopold Verguet, ‘Louka, 1847, ‘Reference: NON-ATL-C-0138-3, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

Bentley said Māori sailors were seen across the globe – from Pacific ports to Sydney, the American whaling ports, Europe and even the Mediterranean.

“They were heavily tattooed, instantly recognisable, and they built reputations as exceptional whalemen.”

Many were given English names by captains – Jacks, Toms and Johns – for discipline and uniformity. While missionaries lamented the loss of meaningful Māori names, Bentley said sailors often took pride in their new identities.

“Once they had an English name, most proudly retained it for the remainder of their lives.”

The darker side

The book does not shy away from the darker side of whaling life. Bentley documents extreme brutality by some captains, including beatings, stabbings and shootings of Māori crew. One infamous case involved the American ship Ploughboy, where Māori sailors were attacked, shot at, and left adrift at sea before surviving to testify in a Sydney court.

“These were incredibly courageous men,” Bentley said. “But if you were vulnerable — sick or isolated — you could be badly mistreated.”

So dangerous were the lives of deep-sea Māori and Kanaka (Pacific Island) whaling seamen during the 1800s that most never returned home.

Despite the dangers, many Māori sailors spent decades at sea. Others found it impossible to readapt to traditional life after years overseas. Some realised that they could not recross cultures and live as Māori and chose to settle beyond New Zealand in places like Sydney and Honolulu.

“The old New Zealand they remembered had changed,” Bentley said. “Some realised they were now Europeans in many ways – and chose to settle in places like Sydney instead.”

Essential

Bentley believes this maritime history is essential to understanding Tauranga and the Bay of Plenty.

“We’re a maritime nation, but we tend to forget that,” he said. “If local historians keep digging and filling in the gaps, Tauranga’s Māori and Pākehā history will become far more coherent — and far more exciting.”

Te Kaewa – The Wanderers is Bentley’s 10th book and available at local Whitcoulls and Paper Plus stores.

1 comment

Congrats!

Posted on 28-01-2026 22:37 | By gaelicc

Well done, Trevor! Another well researched book on our fascinating history.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to make a comment.