One of New Zealand's scallop populations is in dire straits, a survey off the coast of eastern Coromandel reveals, verifying what locals have long feared.

A snapshot survey commissioned by the New Zealand Sport Fishing Council near Opito Bay has discovered its seabeds are unlikely to recover from their depleted state.

Swimming metre by metre towards the shore, divers discovered they would have to swim on average the length of a swimming pool before finding one legal-sized scallop.

It's an alarming result that action group Legasea says could see the Coromandel in a similar position to Marlborough Sounds, a once abundant ecosystem now on to another rāhui after its fourth unsuccessful year.

'We have found that you have to swim 26 square metres to find a single legal scallop,” Legasea spokesman Sam Woolford told Stuff.

'To put that in context, I'm a free diver and on a reasonably healthy seabed I can pick up 10 scallops in a single breath… but I am not swimming 250 metres to find 10 scallops. That's how bad it actually is.

'We've got the Marlborough Sounds, Tasman Bay, Kaipara Harbour and all these areas have been closed to scallop fishing for a long time. Marlborough has been closed again for the fifth year because of the way we've mismanaged our scallop beds.

'These scallop populations have been decimated. They've been overharvested and the commercial dredging has smashed up sea floor.

Divers counted 1571 scallops inside the commercial and recreational areas of Opito Bay.

Of the 1571 scallops, 561 were of legal recreational size (over 100mm) and 1010 under the legal limit.

Woolford says Legasea has put the number of legal-sized scallops down to people respecting the voluntary rāhui over summer.

While 1010 undersized scallops seems like a lot, he said, for the size of the bay, it's not good news.

As well as the distance between scallops, divers noted visible dredge tow-lines that had damaged the sea floor and a lack of other shellfish.

This indicates things 'will probably get worse before they get better”, he says.

'The way in which scallops are reproduced is they spit the eggs out that gets mixed by the current, and it becomes fertilised spat.

'That only happens if you've got a sufficient biomass to have cross-fertilisation, so you've got to have a significant number of scallops in one area for that to work.”

The dive survey was led by the Coromandel Scallop Restoration Team and Dive Zone Whitianga. Qualified divers conducted the data collection and marine scientists completed the report.

It began in April after frustrations around a lack of action from Government on declining scallop numbers, prompting Ngāti Hei to put a voluntary rāhui in Opito Bay waters over the summer period.

The Opito Bay Ratepayers Association raised more than $25,000 to contribute to the project's costs.

Prompted by a large backing from the community, Ngāti Hei has since requested the Ministry for the Environment impose an official rāhui on scallop harvesting for all of eastern Coromandel waters.

To complete the survey, divers swam across the sea floor in segments. They would put a line in the ground, do a rotation around it and metre by metre make their way back to the centre point.

Divers measured every scallop they found and observe its surroundings for signs of dredging and other invertebrates, crustaceans and molluscs.

Ngāti Hei kaumātua Joe Davis said the survey is a baseline to justify the two-year rāhui.

'This data backs up what we've been saying for years,” Davis said.

'If you go back 30 years ago, there used to be tonnes of scallops with regular natural wash-ups which gave us a nice feed, as well as our birdlife.

'The signs are there that we have a declining fishery, and we need to do something about it sooner rather than later.”

He said the results are also a sign that more needs to be done than just a two-year rāhui.

With harmful fishing techniques and dredging still allowed, he said, a two-year ban is unlikely to see results with the lifecycle of a scallop usually around five to six years.

Scallop spat can drift around the sea for up to six months before it finds a home, so the fact that 'we're still dredging outside of this rāhui area may well still have a really negative impact onits resilience or growth opportunities”, Woolford said.

If the rāhui is accepted, Davis said they will do another survey towards the end of the two-year mark to see if there's progress.

'If there's not we will try to extend it, but for mātauranga Māori the true sign of a healthy seabed will come when we have our next storm event and have a wash-up.

'That's when we will know things are coming right again.”

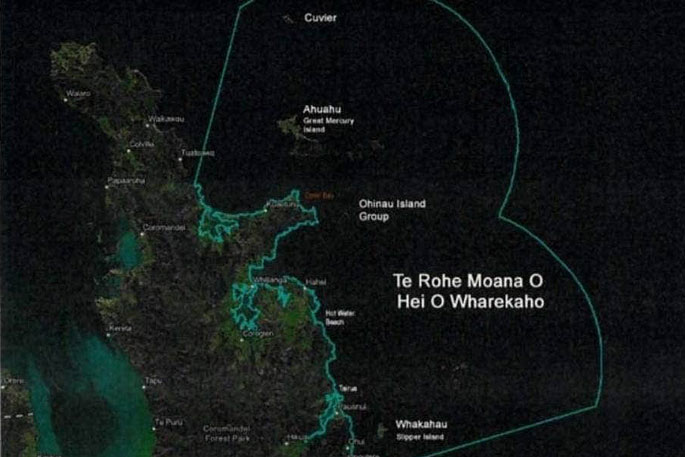

A map showing the area of the proposed closure for eastern Coromandel.

A map showing the area of the proposed closure for eastern Coromandel.

In Coromandel, fishery companies are legally allowed to dredge 50 tonnes of scallops yearly.

For the 2019-2020 season, however, they caught only 13 tonnes – 26 per cent of their total allowable commercial catch – due to scallop population decline.

MPI has not surveyed the scallop beds off Coromandel since 2012, which the quota management is based on.

This year it has contracted Niwa to carry out a thorough scallop survey of Coromandel and Northland recreational scallop areas.

People wanting to make a submission on the proposed two-year closure of scallop harvesting in the eastern Coromandel have until May 17, 5pm.

It would cover waters around Anarake Point, Repanga/Cuvier Island, Ahuahu/Great Mercury Island, Ohinau Island, Alderman Islands, Ruahiwihiwi Point and Whakahau/Slipper Island.

3 comments

Surprise surprise

Posted on 17-05-2021 09:59 | By namxa

Stupid humans.

ban

Posted on 17-05-2021 12:55 | By terry hall

ban all commercial fishing within 200 klm off nz coast now, lets table the minister and make it a political issue.

ban

Posted on 17-05-2021 15:16 | By dumbkof2

as long as the ban applies to everyone

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to make a comment.