During war drills as a wee girl, Gwyneth Jones was given a piece of cork to bite down on.

The thinking at the time was that it would stop her, and other children, from severing their tongues should Japanese invaders bomb their school.

'No-one knows that,” says Gwyneth, 'and that really gets up my nose.”

The author, historian and artist is not easily irritated, but she hears stories coming out of England – via movies, TV and books – about how they coped and how difficult life was, during the war.

'If I ever get anyone from England who says how hard it was, I tell them they would be dead if it wasn't for us,” she says. 'Not only did we fight for them, we fed them.”

No, we weren't bombed, and the suffering can't be compared. 'But we made huge sacrifices,” she adds. 'Men, resources and food. We were rationed so they could eat, and rationing didn't finish ‘til 1952, long after the war.”

Hers is not an attack on the allied cause - it's more about what she believes to be a void in the awareness of New Zealand's history.

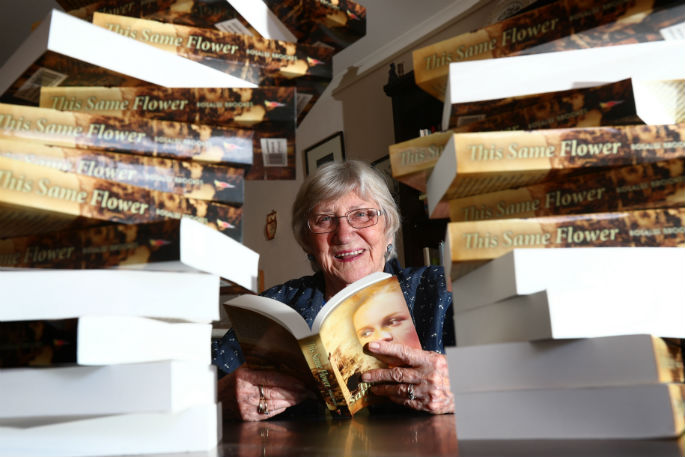

That's why she's written a book - another book - baked with historical fact and iced with romance. ‘This Same Flower' is named after a line from a Robert Herrick poem. 'And this same flower that smiles today, tomorrow will be dying.”

She's drawn on her own childhood for this war-time tale, set against the backdrop of Glen Afton, a coal mining village west of Huntly, during the war.

'The miners were heroes,” she explains. 'They were very, very brave. They worked 24/7, often back shifting, to keep this country running because it was a coal-fired country.”

Had the enemy thrust into Raglan, as it was believed they would, the Waikato mines would have been a natural target. 'They would have been wiped out and the country would have been crippled.”

It was such information that was thrown up while she was researching her book ‘At the Coalface', a history of Huntly's coal mines and townships.

If the well-read author didn't know these things, then others wouldn't either. 'And they should,” says Gwyneth.

'They converted the old Glen Massey pottery into an air force base, and there's hardly anyone who knows there was an American Air Force base at Glen Massey during the war.”

Her book puts that right, as it does with many other intriguing historical insights.

'I drew a lot on my childhood, but it's exaggerated,” says the author. But not the fact that her father failed his Air Force medical and was 'man-powered 'into the pottery at Glen Afton to make toilet bowls and hand basins for a military camp. 'Well, Dad was an alcoholic,” she says, 'and he did go off on benders.”

Had he known his excessiveness, his intemperance, would be a thread of a novel one day - one written by his daughter - he may have mended his ways.

But it's against this backdrop of mines, war and threats of invasion that Gwyneth Jones spins the story of Megan Morgan, or Meggie.

'That was my wartime childhood,” she says. It was black curtains and war drills, because we were a vulnerable school near the mines that the Japanese might just bomb.

'We each had little bags with sticking plasters, scissors, cotton wool to protect our ears from bomb blasts and cork to stop us biting off our tongues.”

When the bell rang, they leapt into the trenches behind their school. They're the facts, but then there's the slow unravelling romance and the companionship Meggie finds with the handsome Simon Griffith. The author re-iterates her point. 'People don't know these things and they should. We read how terrible it was in England and Australia, but we went through all those things.”

A little girl called Meggie, an exaggeration of the author herself, helps us understand some of the unknowns of the New Zealand war effort.

0 comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to make a comment.