You might not think so given a spate of recent headlines about ramraiders, smash-and-grabbers and other kinds of young criminals, but the youth justice system in New Zealand actually works pretty well.

That's the verdict of experts canvassed by Stuff following the announcement by police on Thursday that there had been mass arrests of young people in Waikato and Auckland for a recent swathe of violent crime.

However, there are some aspects of the system that are not particularly effective – mainly the speed at which young offenders are processed in the Youth Court – and Covid and the influence of social media have thrown a few unwelcome spanners into the works.

An apparent increase in ramraids in particular has trained the public spotlight on recidivist offenders, and has raised questions over whether the youth justice process has any power as a deterrent for future offenders.

Robbers armed with hammers and an axe targeted a jewellery shop at The Base Hamilton in front of shoppers. (This video was first published on September 25, 2022 on Stuff.co.nz)

A secondary concern is the lack of visibility of what happens in the Youth Court.

One of the main tenets of the adult criminal courts in New Zealand is that justice must be seen to be done. Offenders have to work hard to justify why their identities should be suppressed on either an interim or permanent basis.

However, a veil surrounds the Youth Court, where the names of offenders are automatically permanently suppressed by law and the media must get the express permission of the judge before covering.

'I think New Zealand has it right,” Lisa Tompson, a senior lecturer at Te Puna Haumaru, the New Zealand Institute for Security and Crime Science based at Waikato University, and whose area of expertise is crime prevention.

Michael Hill Jeweller in Takapuna following their fourth smash and grab attack in recent months. Photo: Chris McKeen/Stuff.

'There is a growing body of evidence that stigmatising people with the ‘criminal' label may do more harm than good. If we consistently tell someone ‘You are a criminal, you are a criminal, you are a criminal' then eventually they accept that view. Some even come to see it as a badge of honour.”

In some cultures around the world, such as Japan, an approach of naming and shaming was a very effective deterrent. However, in western societies including New Zealand it was far less effective 'and could backfire”.

Although she did not have access to figures on the current rates of reoffending among young criminals, Tompson was well-versed in an area known as 'deterrence theory”.

There were two main kinds of youth offenders, she says. One was the adolescent opportunists whose brains were not fully developed – 'and these are the people who should be given a chance”.

Lisa Tompson, a senior lecturer at Te Puna Haumaru, the New Zealand Institute for Security and Crime Science based at Waikato University, says the 'naming and shaming” approach to youth crime is not effective in New Zealand. Photo: Supplied/Stuff.

The other was what she termed 'life-persistent offenders – the hard core” who took part in more and more serious offending.

Ramraids, which were 'a much more purposeful crime” generally fitted into that category of offender.

There were three main elements to deterrence theory: Severity, celerity and certainty.

There was no evidence to suggest that the severity of punishments had any influence on stopping ongoing offending, says Tompson. A good illustration of that was the US states that enforced the death penalty for homicide all had higher homicide rates.

'Celerity” referred to the swiftness with which justice was meted. If the courts took too long to deal with young offenders then those youngsters did not associate their eventual punishment with the crime they had committed.

'If it takes too long, then it isn't reinforced as a negative consequence of their actions ... It's like if you tell a dog to sit and then give it a treat. If you tell the dog to sit and then give it a treat half an hour later, it does not associate getting the treat with the act of sitting.”

'Certainty” related to the perception they might get caught.

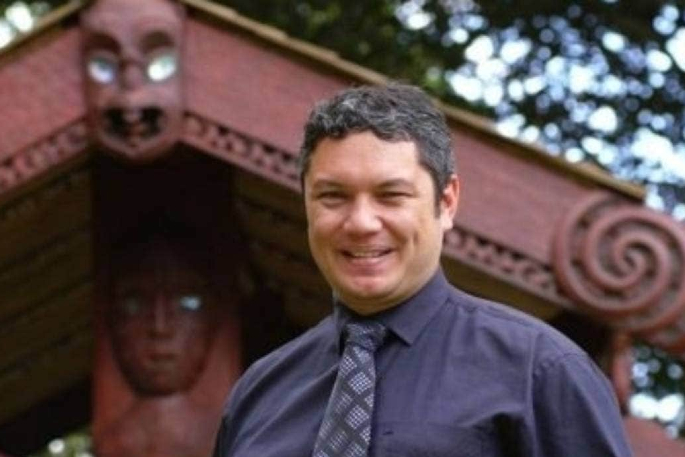

Clinical psychology senior lecturer Armon Tamatea. Photo: Supplied/Stuff.

'Most people contemplating a crime do not commit the crime if they think there is a realistic chance they might get caught ... That's one of the things we need to work on.”

Armon Tamatea, another Waikato University senior lecturer working in the field of clinical psychology, says since 2007 there had been 'an uninterrupted decline” in the number of youths being sentenced in the courts and going to prison.

'Ramraids and smash-and-grabs are not new ... The recent narrative has blamed young people for these issues, but there's much more to it than that. To solve the problem you need to look at how these young people came to be that way.

'Youth justice is a set of complex issues and requires more than just systems to solve. The issues [for young offenders] often start in communities and multiple generations ago. It requires an almost ecological change.”

One of the more recent factors was the Covid pandemic, which had led to youngster's schooling – and therefore their connections to their peer groups and adult role models – being disrupted or severed.

Another factor was the influence of social media, particularly TikTok.

'Young people care greatly about what their peers think of them.”

The behaviour of young people was – and always has been – either tacitly or actively encouraged to be copied or emulated, he says.

'It's like people who do the dances. They copy the dance and then post it up. This risky behaviour – the smash-and-grabs – is no different. Everyone wants to impress everyone else.”

Connected to this was cellphone and security camera footage of crimes, which for youth offenders could provide the same kind of thrilling evidence of their endeavours.

'Security cameras record the crimes, but they don't really act as a deterrent – even though that's part of their purpose.

'It's a real paradox.”

1 comment

How about

Posted on 22-10-2022 20:10 | By Johnney

Naming their parents or caregivers. Might encourage them to know what their charges are up to in the middle of the night.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to make a comment.